Clarifying the benefits of shared single-user bathrooms in higher ed residence halls

For college and university facilities decision-makers and residential life professionals, determining the right bathroom accommodation for first year student residents is a crucial contributor to creating successful residential environments – particularly in the face of the monumental challenges posed to occupant health during a global pandemic. While the cramped and institutional community bathroom designs that became standard issue over 50 years ago have long since fallen out of favor, the prevailing wisdom is to merely update the community bathroom model with slightly enhanced privacy through fixture compartmentalization and more spa-like design aspects. This is a common preconception rooted in concerns over cost and square foot efficiency. We have learned there is a more transformative solution that meets all the right value criteria – the shared single-user bathroom … which surpasses even retooled and updated versions of the traditional community bathroom in terms of efficiency, safety, privacy, flexibility, inclusivity, accessibility, and cost. To explain, we will delve into each of those aspects in more detail. First, we need to understand the planning principles involved in bathroom design.

How Many Plumbing Fixtures?

As residential life designers, we understand the importance of efficiency in all matters because it has such a big impact on cost. To maximize efficiency, the required number of plumbing fixtures must be determined.

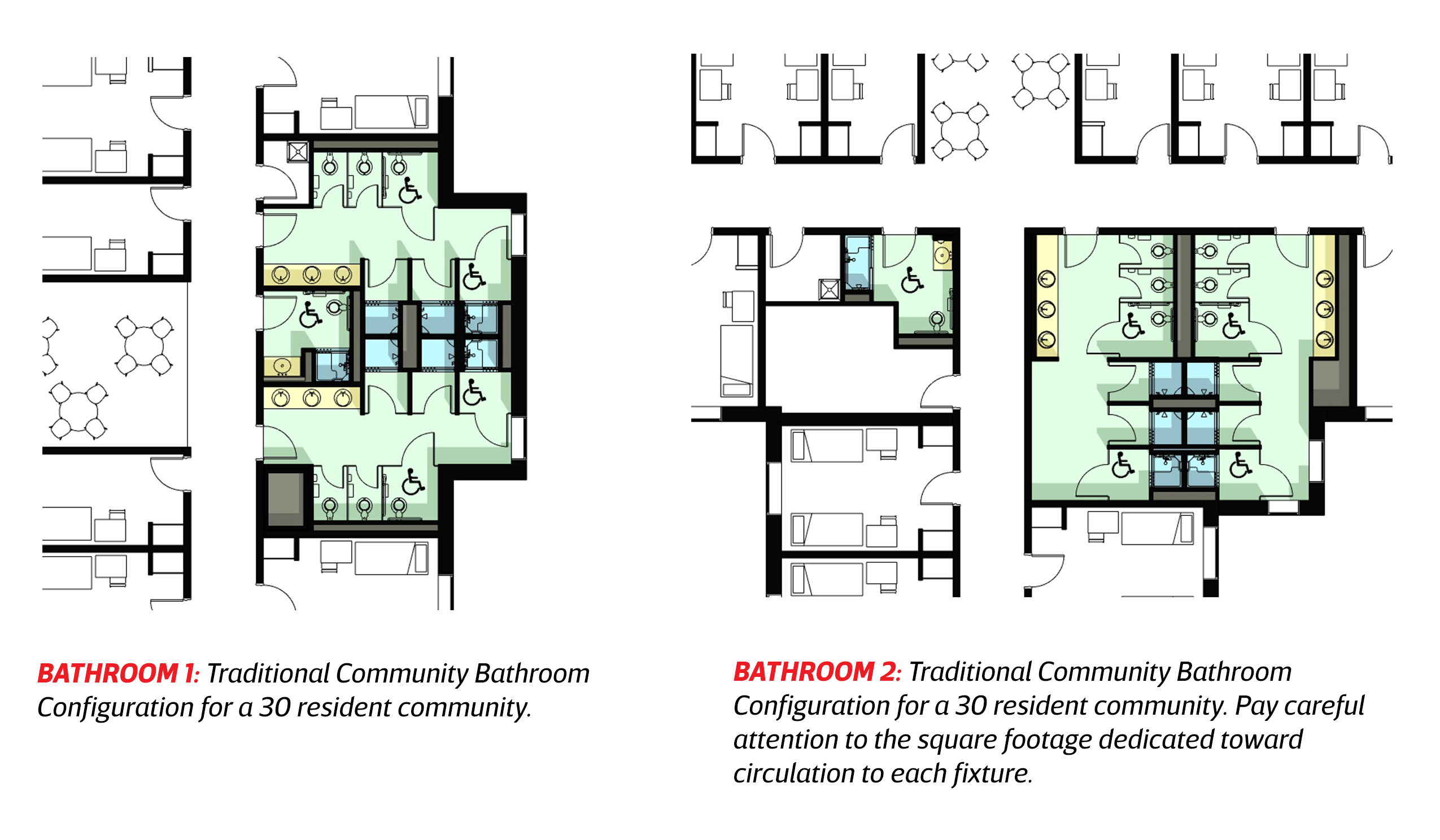

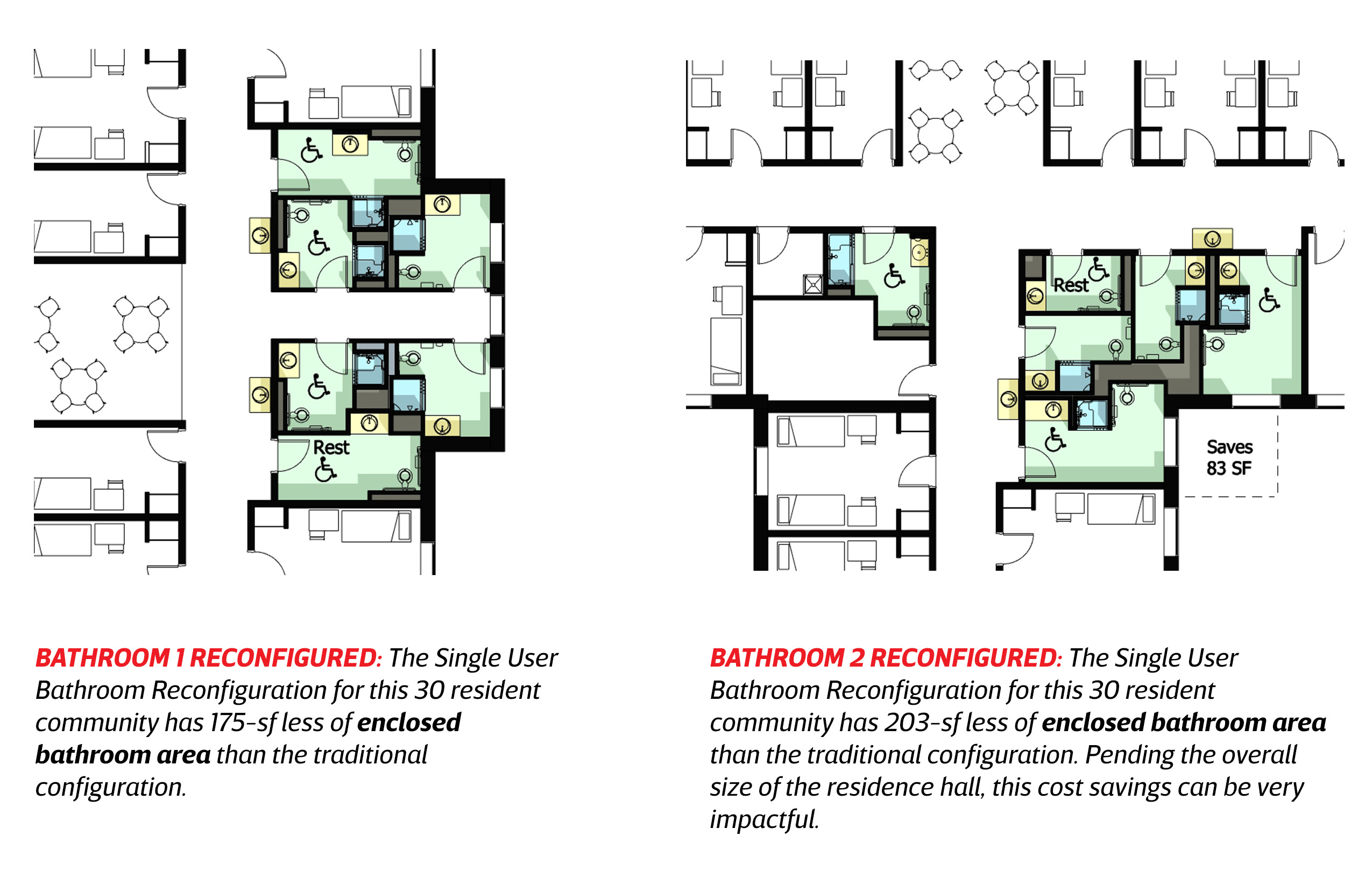

In our experience working with multiple higher education institutions, the optimum baseline plumbing fixture to student ratio that is generally best suited for traditional residence halls (particularly for first year students) is 1:6. This ratio exceeds most building code requirements, but rarely do meeting code minimum quantities result in satisfactory results. The bathroom layout comparisons illustrated in this article are based on a hypothetical residential advisor staff population of 30 residents. Here are examples illustrating how to calculate the necessary plumbing fixture counts for both types of bathroom arrangements:

Traditional Community Bathroom Approach:

For 30 residents, we divide the population in half based on an equal gender split, so 15 divided by 6 = 2.5 (we must round up to 3 fixtures in each bathroom). Given the importance of gender inclusivity, at least one full single user bathroom should also be included for this population. The resulting plumbing fixture counts for this type of bathroom accommodation results in 7 showers, 7 sinks, and 7 water closets (21 total fixtures). One other consideration with this arrangement is the likelihood that the RA might be assigned to a single bedroom with a private bathroom, which will increase the total fixture count.

Shared Single-User Bathroom Approach:

Using the same 30 RA population, we would divide 30 by 6 = 5 (gender parity and inclusivity is already satisfied with this approach). To augment the flexibility of this arrangement, we have found it works best to include two hand sinks near the bathroom area plus one restroom (with sink and water closet only). This results in more of a weighted distribution of plumbing fixtures that better caters to demand of residents – 5 showers, 8 sinks, and 6 water closets (18 total fixtures).

Bottom line – the needs of a student residential population are met more efficiently (occupying the same, or smaller floor area) with fewer plumbing fixtures (saving cost) and improved flexibility of use for the occupants.

Safety

Single-user bathrooms offer a more private accommodation, which helps ease the emotional stress in young students as they transition from living at home to being on campus, but there are also clear benefits from an overall occupant health standpoint. In April of this year, the American Society of Heating, Refrigerating and Air-Conditioning Engineers published a document titled ASHRAE Position Document on Infectious Aerosols, which takes a deep dive into the topic of infectious aerosols. The smaller droplets of SARS-CoV-2 can remain airborne for up to three hours. The simple action of flushing a toilet circulates particles into the air making the multiple users in the traditional community bathroom vulnerable to contagions. Also, maintaining the proper social distancing recognized by ASHRAE in these settings is particularly challenging. In contrast, shared single-user bathrooms greatly reduce the vulnerability of occupants to cross-contamination via airborne droplets. Additionally, providing sinks in common areas, like hallways near the bathrooms, goes a long way in making hand-washing more visible, accessible, and convenient.

Flexibility + Inclusivity

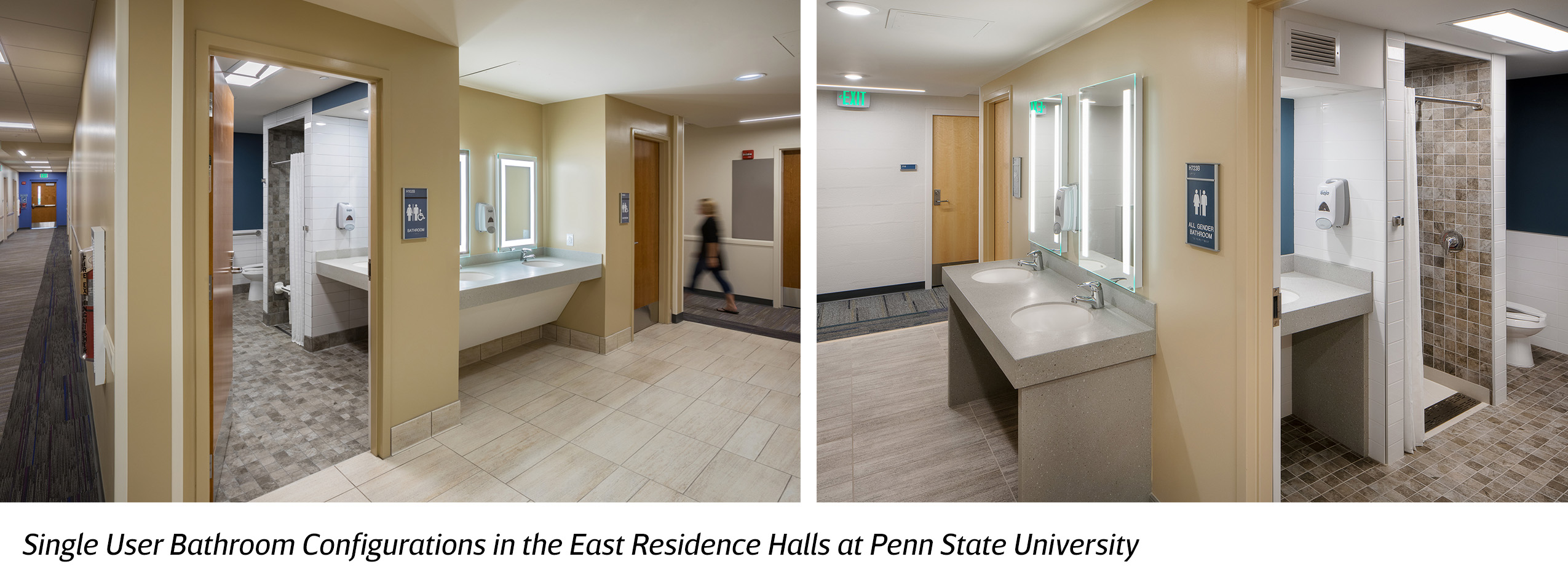

Private bathrooms solve gender and inclusivity concerns in the fairest way possible. An institution no longer needs to assign residential communities, residential floors, or residential buildings as gender specific. Room assignments for residents can be tricky so eliminating a constraint from the equation goes a long way in helping to maximize flexible facility planning. There are hybrid design solutions that attempt to solve gender inclusivity like providing a private bathroom in addition to the community bathrooms to serve a residential community; however, residents quickly pick up on the preferences of fellow residents. Thus, hybrid solutions are far from being fair compared to the inclusivity of single-user bathrooms.

Accessibility

The 50% cluster rule of private bathrooms (IBC 2018, Section 1109.2, Exception 3) works wonders when designing efficient single-user bathrooms. This building code section states when multiple single-user bathrooms are clustered in a single location at least 50% of those bathrooms must be accessible. There are design tricks with separating accessible bathrooms with standard bathrooms that allow dimensions to be tightened and refined; thus reaching convincing efficiency numbers. The tightest standard bathroom is far superior compared to a fixture located in the stall of a community bathroom.

Cost

In terms of first cost, shared single-user bathrooms are either cost neutral or a cost savings compared to traditional community bathrooms. Much depends on the floor plan arrangement and space needed for the bathrooms. Long-term cost can be tough to predict accurately, but there are important design features that can be considered with an eye towards mitigating the ongoing costs of cleaning and maintenance:

- Full height ceramic tile on all walls

- Hose bibs below sinks

- Easily removable drain covers (no special tools)

- Flood-testing of all bathroom waterproofing installations during construction

- Water-cleanable epoxy grout on walls and floors

- Diverters and fixed shower heads in addition to hand-held devices in accessible shower stalls

- Shower seats with legs

- Floor-mounted water closets

Of course, each campus project has a unique set of circumstances and it may not always make sense to adopt the shared single-user bathroom model. But it is certainly worth considering. For anyone interested in learning more about the occupant usage and maintenance of this type of amenity, we are happy to connect you with knowledgeable housing and facility clients with whom we have collaborated who would be happy to share lessons learned. Feel free to comment and let’s talk!

By: Nick Naeger

By: Nick Naeger