Marina Curac is a designer in our North Carolina office. She recently had the opportunity to take extended time off to see an exhibition at MoMA in New York City, travel, explore, and see her family in her home country of Croatia. Through her travels, Marina discovered a renewed sense of wonder and a unique connection to her heritage as she describes in the following journal entry.

Architecture of Split, Croatia

America knows Croatia and its neighbors for two things: war and basketball. They know about the war in the 1990s that Bill Clinton sent troops to, and they know us from a few great NBA players like Petrovic, Divac, Radja, Kukoc. Some people might also know us for our beautiful nature, but that’s still not common knowledge.

I’ve spent almost a decade in America. I studied architecture in Pennsylvania and got my master’s in St. Louis. Now, I live in Asheville, North Carolina and work at a Mackey Mitchell satellite office. But no matter where I go, I rarely meet anyone who knows us for more than war and basketball.

I find it sad that people here know so little about my home. Croatia and its neighbors have much to offer, yet somehow we always seem off the radar. That’s why it was such an amazing surprise when I discovered MoMA would organize an exhibit on post-WWII architecture in Yugoslavia, titled ‘Toward a Concrete Utopia: Architecture in Yugoslavia, 1948–1980’. I had to go see it for myself.

My husband and I already had plans to visit our families and relatives in Europe over the summer, so on our way out of the country, we made a brief stop in New York.

As we entered the exhibit, I teared up. I was so moved and proud. Finally — a big-time museum like MoMA seeing something valuable from my little part of the world.

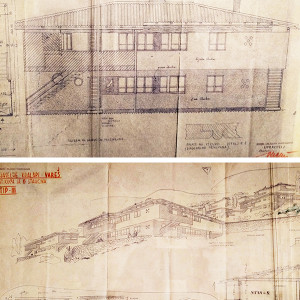

The exhibit featured large architectural drawings, detailed physical models, period photographs of finished buildings, and examples of the everyday furniture and appliances you would find in these hotels, apartments, and office buildings.

I got to see the original drafting of a famous stadium in Split where I’d watched soccer matches with my family. Among the furnishings was a standard socialist telephone I remembered my grandma having in her house. They even had a replica of a popular modular kiosk that you could still see in some places in Croatia and its neighboring countries. What hit home for me the most was simply seeing building plans in my native tongue — something I’d never seen during my academic life in America. These spoke to my heart as much as they did to my mind.

The story the exhibit told wove through the optimism and excitement present in the new post WWII nation of Yugoslavia. People were leaving their homes in rural areas and rushing to cities to live in high rises, embracing the promise of modernism and collective living.

Winston Churchill once famously said, “we shape our buildings; thereafter they shape us.” What is shown at MoMA are witnesses of another era. Fascination with concrete was fueled by inexpensive and abundant raw materials. This seemingly monolithic medium allowed architectural scene to develop an outstanding level of diversity and experimentation. Deep connection between architecture and quality of people’s life was constantly emphasized. Better architecture meant a happier life—life full of hopes, achievement and dreams for better tomorrow.

Even though the entire exhibit seeps with socialist agenda and its utopia, it is only at the very end of the exhibition journey that a visitor sees artistic pieces and monuments that are directly celebrating Yugoslavian political regime and its anti fascist movement.

These monuments celebrate heroes who fell fighting for ideas of freedom, unity and brotherhood. As I was observing these expressive pieces, I thought about how these people had given their lives for a unified Yugoslavia, and how less than 50 years later, their children and grandchildren would tear themselves apart in a bloody civil war that lasted for almost a decade. Did they all die in vain? Was the Concrete Utopia always a far-flung fantasy?

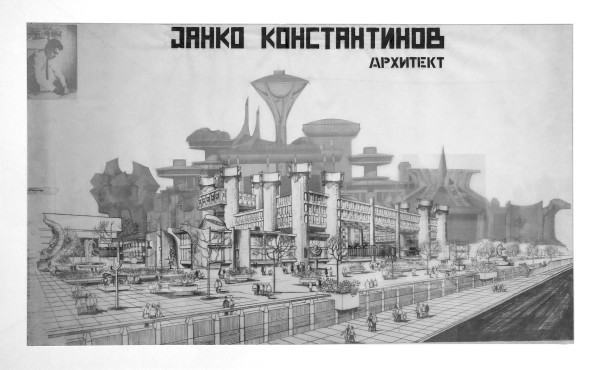

Exhibition poster for the Post Office and Telecommunications Center in Skopje, Macedonia, designed by Macedonian Architect Janko Konstantinov (click to expand)

Mixed with joy, thrill and pride of works of Magas, Ravnikar, and Neidhardt, I left the exhibition. That same day, while eating pizza and gelato with my husband, I watched as the Croatian national football team lost in the finals of the 2018 World Cup.

But perhaps it’s better to say they won second place. Our sports, like our architecture, holds out hope for a better, brighter future.

Having spent a month travelling, exploring, being with loved ones made me feel so enriched. I learned a lot about architectural heritage which was not that well known, and I was so excited to see it in the world’s limelight, too. It was a precious experience to connect what we saw at MoMA with the natural and historic settings that influenced the artwork. It reminded me once again of the importance of travelling, being curious, brave and adventurous – you never know what you’re going to see around that corner, over that hill, or through that cloud.

More importantly, it renewed my sense of wonder of how the spaces we design today will impact us tomorrow. As Croatians have experienced, with careful intent, architecture can bring hope and promise for a better future.

By: Marina Curac

By: Marina Curac